The Goose-Girl There was once upon a time

an old Queen whose husband had been dead for many years,

and she had a beautiful daughter.

When the princess grew up she was betrothed to a prince who lived at a great distance. When the time came for her to be married, and she had to journey forth into the distant kingdom, the aged Queen packed up for her many costly vessels of silver and gold, and trinkets also of gold and silver; and cups and jewels - in short, everything which appertained to a royal dowry,

for she loved her child with all her heart.

She likewise sent her maid-in-waiting, who was to ride with her, and hand her over to the bridegroom, and each had a horse for the journey, but the horse of the King's daughter was called Falada, and could speak. So when the hour of parting had come, the aged mother went into her bedroom, took a small knife and cut her finger with it until it bled, then she held a white handkerchief to it into which she let three drops of blood fall, gave it to her daughter and said, "Dear child, preserve this carefully, it will be of service to you on your way."

So they took a sorrowful leave of each other; the princess put the piece of cloth in her bosom, mounted her horse,

and then went away to her bridegroom.

After she had ridden for a while she felt a burning thirst, and said to her waiting-maid. "Dismount, and take my cup which thou hast brought with thee for me, and get me some water from the stream, for I should like to drink." "If you are thirsty," said the waiting-maid, "get off your horse yourself, and lie down and drink out of the water, I don't choose to be your servant."

So in her great thirst the princess alighted, bent down over the water in the stream and drank, and was not allowed to drink out of the golden cup. Then she said, "Ah, Heaven!" and the three drops of blood answered, "If thy mother knew this, her heart would break,"

But the King's daughter was humble, said nothing, and mounted her horse again. She rode some miles further, but the day was warm, the sun scorched her, and she was thirsty once more,

and when they came to a stream of water, she again cried to her waiting - maid, "Dismount and give me some water in my golden cup," for she had long ago forgotten the girl's ill words.

But the waiting-maid said still more haughtily, "If you wish to drink, drink as you can, I don't choose to be your maid."

Then in her great thirst the King's daughter alighted, bent over the flowing stream, wept and said, "Ah, Heaven!" and the drops of blood again replied, "If thy mother knew this, her heart would break." And as she was thus drinking and leaning right over the stream, the handkerchief with the three drops of blood fell out of her bosom, and floated away with the water without her observing it, so great was her trouble.

The waiting-maid, however, had seen it, and she rejoiced to think that she had now power over the bride, for since the princess had lost the drops of blood, she had become weak and powerless.

So now when she wanted to mount her horse again, the one that was called Falada, the waiting-maid said, "Falada is more suitable for me, and my nag will do for thee," and the princess had to be content with that. Then the waiting-maid, with many hard words, bade the princess exchange her royal apparel for her own shabby clothes; and at length she was compelled to swear by the clear sky above her, that she would not say one word of this to anyone at the royal court, and if she had not taken this oath she would have been killed on the spot. But Falada saw all this, and observed it well. The waiting-maid now mounted Falada, and the true bride the bad horse, and thus they travelled onwards, until at length they entered the royal palace.

There were great rejoicings over her arrival, and the prince sprang forward to meet her, lifted the waiting-maid from her horse, and thought she was his consort. She was conducted upstairs, but the real princess was left standing below.

Then the old king looked out of the window and saw her standing in the courtyard, and saw how dainty and delicate and beautiful she was, and instantly went to the royal apartment, and asked the bride about the girl she had with her who was standing down below in the courtyard, and who she was?

"I picked her up on my way for a companion; give the girl something to work at, that she may not stand idle."

But the old King had no work for her, and knew of none, so he said, "I have a little boy who tends the geese, she may help him." The boy was called Conrad, and the true bride had to help him to tend the geese. Soon afterwards the false bride said to the young King, "Dearest husband, I beg you to do me a favour."

He answered. "I will do so most willingly." "Then send for the knacker, and have the head of the horse on which I rode here cut off, for it vexed me on the way." In reality, she was afraid that the horse might tell how she had behaved to the King's daughter. Then she succeeded in making the King promise that it should be done, and the faithful Falada was to die; this came to the ears of the real princess, and she secretly promised to pay the knacker a piece of gold if he would perform a small service for her.

There was a great dark-looking gateway in the town, through which morning and evening she had to pass with the geese: would he be so good as to nail up Falada's head on it, so that she might see him again, more than once. The knacker's man promised to do that, and cut off the head, and nailed it fast beneath the dark gateway.

Early in the morning, when she and Conrad drove out their flock beneath this gateway, she said in passing,

"Alas, Falada, hanging there!" Then the head answered,

"Alas, young Queen, how ill you fare! If this your tender mother knew, Her heart would surely break in two."

Then they went still further out of the town, and drove their geese into the country. And when they had come to the meadow, she sat down and unbound her hair which was like pure gold, and Conrad saw it and delighted in its brightness, and wanted to pluck out a few hairs.

Then she said, "Blow, blow, thou gentle wind, I say, Blow Conrad's little hat away, And make him chase it here and there, Until I have braided all my hair, And bound it up again."

And there came such a violent wind that it blew Conrad's hat far away across country, and he was forced to run after it.

When he came back she had finished combing her hair and was putting it up again, and he could not get any of it.

Then Conrad was angry, and would not speak to her, and thus they watched the geese until the evening, and then they went home.

Next day when they were driving the geese out through the dark gateway, the maiden said, "Alas, Falada, hanging there!"

Falada answered, "Alas, young Queen, how ill you fare! If this your tender mother knew, Her heart would surely break in two." And she sat down again in the field and began to comb out her hair, and Conrad ran and tried to clutch it, so she said in haste, "Blow, blow, though gentle wind, I say, Blow Conrad's little hat away, And make him chase it here and there, Until I have braided all my hair, And bound it up again."

Then the wind blew, and blew his little hat off his head and far away, and Conrad was forced to run after it, and when he came back, her hair had been put up a long time, and he could get none of it, and so they looked after their geese till evening came.

But in the evening after they had got home, Conrad went to the old King, and said, "I won't tend the geese with that girl any longer!" "Why not?" inquired the aged King.

"Oh, because she vexes me the whole day long."

Then the aged King commanded him to relate what it was that she did to him. And Conrad said, "In the morning when we pass beneath the dark gateway with the flock, there is a sorry horse's head on the wall, and she says to it, "Alas, Falada, hanging there!" And the head replies, "Alas, young Queen, how ill you fare!

If this your tender mother knew, Her heart would surely break in two." And Conrad went on to relate what happened on the goose pasture, and how when there he had to chase his hat.

The aged King commanded him to drive his flock out again next day, and as soon as morning came, he placed himself behind the dark gateway, and heard how the maiden spoke to the head of Falada, and then he too went into the country, and hid himself in the thicket in the meadow. There he soon saw with his own eyes the goose-girl and the goose-boy bringing their flock, and how after a while she sat down and unplaited her hair, which shone with radiance. And soon she said, "Blow, blow, thou gentle wind,

I say, Blow Conrad's little hat away, And make him chase it here and there, Until I have braided all my hair, And bound it up again." Then came a blast of wind and carried off Conrad's hat,

so that he had to run far away, while the maiden quietly went on combing and plaiting her hair, all of which the King observed. Then, quite unseen, he went away, and when the goose-girl came home in the evening, he called her aside, and asked why she did all these things. "I may not tell you that, and I dare not lament my sorrows to any human being, for I have sworn not to do so by the heaven which is above me; if I had not done that, I should have lost my life." He urged her and left her no peace, but he could draw nothing from her.

Then said he, "If thou wilt not tell me anything, tell thy sorrows to the iron-stove there," and he went away.

Then she crept into the iron-stove, and began to weep and lament, and emptied her whole heart, and said, "Here am I deserted by the whole world, and yet I am a King's daughter, and a false waiting-maid has by force brought me to such a pass that I have been compelled to put off my royal apparel, and she has taken my place with my bridegroom, and I have to perform menial service as a goose-girl. If my mother did but know that, her heart would break." The aged King, however, was standing outside by the pipe of the stove, and was listening to what she said, and heard it. Then he came back again, and bade her come out of the stove. And royal garments were placed on her,

and it was marvellous how beautiful she was!

The aged King summoned his son, and revealed to him that he had got the false bride who was only a waiting-maid, but that the true one was standing there, as the sometime goose-girl. The young King rejoiced with all his heart when he saw her beauty and youth, and a great feast was made ready to which all the people and all good friends were invited. At the head of the table sat the bridegroom with the King's daughter at one side of him, and the waiting-maid on the other, but the waiting - maid was blinded, and did not recognize the princess in her dazzling array.

When they had eaten and drunk, and were merry, the aged King asked the waiting - maid as a riddle, what a person deserved who had behaved in such and such a way to her master, and at the same time related the whole story, and asked what sentence such an one merited? Then the false bride said: "She deserves no better fate than to be stripped entirely naked, and put in a barrel which is studded inside with pointed nails, and two white horses should be harnessed to it, which will drag her along through one street after another, till she is dead." "It is thou," said the aged King, "

and thou hast pronounced thine own sentence, and thus shall it be done unto thee."

And when the sentence had been carried out, the young King married his true bride, and both of them reigned over their kingdom in peace and happiness.

by |The Brothers Grimm

~The Goose Girl

~The Three Little Pigs

The animal I really dig,

Above all others is the pig.

Pigs are noble. Pigs are clever,

Pigs are courteous. However,

Now and then, to break this rule,

One meets a pig who is a fool.

What, for example, would you say,

If strolling through the woods one day,

Right there in front of you you saw

A pig who'd built his house of STRAW?

The Wolf who saw it licked his lips,

And said, "That pig has had his chips."

"Little pig, little pig, let me come in!"

"No, no, by the hairs on my chinny-chin-chin!"

"Then I'll huff and I'll puff and I'll blow your house in!"

The little pig began to pray,

But Wolfie blew his house away.

He shouted, "Bacon, pork and ham!

Oh, what a lucky Wolf I am!"

And though he ate the pig quite fast,

He carefully kept the tail till last.

Wolf wandered on, a trifle bloated.

Surprise, surprise, for soon he noted

Another little house for pigs,

And this one had been built of TWIGS!

"Little pig, little pig, let me come in!"

"No, no, by the hairs on my chinny-chin-chin!"

"Then I'll huff and I'll puff and I'll blow your house in!"

The Wolf said, "Okay, here we go!"

He then began to blow and blow.

The little pig began to squeal.

He cried, "Oh Wolf, you've had one meal!

Why can't we talk and make a deal?

The Wolf replied, "Not on your nelly!"

And soon the pig was in his belly.

"Two juicy little pigs!" Wolf cried,

"But still I'm not quite satisfied!

I know how full my tummy's bulging,

But oh, how I adore indulging."

So creeping quietly as a mouse,

The Wolf approached another house,

A house which also had inside

A little piggy trying to hide.

"You'll not get me!" the Piggy cried.

"I'll blow you down!" the Wolf replied.

"You'll need," Pig said, "a lot of puff,

And I don't think you've got enough."

Wolf huffed and puffed and blew and blew.

The house stayed up as good as new.

"If I can't blow it down," Wolf said,

I'll have to blow it up instead.

I'll come back in the dead of night

And blow it up with dynamite!"

Pig cried, "You brute! I might have known!"

Then, picking up the telephone,

He dialed as quickly as he could

The number of red Riding Hood.

"Hello," she said. "Who's speaking? Who?

Oh, hello, Piggy, how d'you do?"

Pig cried, "I need your help, Miss Hood!

Oh help me, please! D'you think you could?"

"I'll try of course," Miss Hood replied.

"What's on your mind...?" "A Wolf!" Pig cried.

"I know you've dealt with wolves before,

And now I've got one at my door!"

"My darling Pig," she said, "my sweet,

That's something really up my street.

I've just begun to wash my hair.

But when it's dry, I'll be right there."

A short while later, through the wood,

Came striding brave Miss Riding Hood.

The Wolf stood there, his eyes ablaze,

And yellowish, like mayonnaise.

His teeth were sharp, his gums were raw,

And spit was dripping from his jaw.

Once more the maiden's eyelid flickers.

She draws the pistol from her knickers.

Once more she hits the vital spot,

And kills him with a single shot.

Pig, peeping through the window, stood

And yelled, "Well done, Miss Riding Hood!"

Ah, Piglet, you must never trust

Young ladies from the upper crust.

For now, Miss Riding Hood, one notes,

Not only has two wolfskin coats,

But when she goes from place to place,

She has a PIGSKIN TRAVELING CASE.

by Roald Dahl

Image by Leonard Leslie Brooke

~The Girl Who Trod on the Loaf

You have quite likely heard of the girl who trod on a loaf so as not to soil her pretty shoes, and what misfortunes this brought upon her. The story has been written and printed, too.

She was a poor child, but proud and arrogant, and people said she had a bad disposition. When but a very little child, she found pleasure in catching flies, to pull off their wings and make creeping insects of them. And she used to stick May bugs and beetles on a pin, then put a green leaf or piece of paper close to their feet, so that the poor animals clung to it, and turned and twisted as they tried to get off the pin.

"The May bug is reading now," little Inger would say.

"See how it turns the leaves!"

As she grew older she became even worse instead of better;

but she was very pretty, and that was probably her misfortune. Because otherwise she would have been disciplined more than she was.

"You'll bring misfortune down upon you," said her own mother to her. "As a little child you often used to trample on my aprons;

and when you're older I fear you'll trample on my heart."

And she really did.

Then she was sent into the country to be in the service of people of distinction. They treated her as kindly as if she had been their own child and dressed her so well that she looked extremely beautiful and became even more arrogant.

When she had been in their service for about a year, her mistress said to her, "You ought to go back and visit your parents, little Inger."

So she went, but only because she wanted to show them how fine she had become. But when she reached the village, and saw the young men and girls gossiping around the pond, and her mother sat resting herself on a stone near by, with a bundle of firewood she had gathered in the forest, Inger turned away; she was ashamed that one dressed as smartly as she should have for a mother such a poor, ragged woman who gathered sticks for burning. It was without reluctance that she turned away;

she was only annoyed.

Another half year went by.

"You must go home someday and visit your old parents, little Inger," said her mistress. "Here's a large loaf of white bread to take them. They'll be happy to see you again."

So Inger put on her best dress and her fine new shoes and lifted her skirt high and walked very carefully, so that her shoes would stay clean and neat, and for that no one could blame her. But when she came to where the path crossed over marshy ground, and there was a stretch of water and mud before her, she threw the bread into the mud, so that she could use it as a steppingstone and get across with dry shoes. But just as she placed one foot on the bread and lifted the other up, the loaf sank in deeper and deeper, carrying her down until she disappeared entirely, and nothing could be seen but a black, bubbling pool! That's the story.

But what became of her? She went down to the Marsh Woman, who brews down there. The Marsh Woman is an aunt of the elf maidens, who are very well known. There have been poems written about them and pictures painted of them, but nobody knows much about the Marsh Woman, except that when the meadows begin to reek in the summer the old woman is at her brewing down below. Little Inger sank into this brewery, and no one could stand it very long there. A cesspool is a wonderful palace compared with the Marsh Woman's brewery. Every vessel is reeking with horrible smells that would turn a human being faint, and they are packed closely together; but even if there were enough space between them to creep through, it would be impossible because of the slimy toads and the fat snakes that are creeping and slithering along. Into this place little Inger sank, and all the horrible, creeping mess was so icy cold that she shivered in every limb. She became more and more stiff, and the bread stuck fast to her, drawing her as an amber bead draws a slender thread.

The Marsh Woman was at home, for the brewery was being visited that day by the devil and his great-grandmother, the latter a very poisonous old creature who was never idle. She never goes out without taking some needlework with her, and she had brought some this time. She was sewing bits of leather to put in people's shoes, so that they should have no rest. She embroidered lies, and worked up into mischief and slander thoughtless words that would otherwise have fallen harmlessly to the ground. Yes, she could sew, embroider, and weave, that old great-grandmother!

She saw Inger, then put on her spectacles and looked again at her. "That girl has talent," she said. "Let me have her as a souvenir of my visit here; she will make a suitable statue in my great-grandchildren's antechamber." And she was given to her!

Thus little Inger went to hell! People don't always go directly down there; they can go by a roundabout way, when they have the necessary talent.

It was an endless antechamber. It made one dizzy to look forward and dizzy to look backward, and there was a crowd of anxious, exhausted people waiting for the gates of mercy to be opened for them. They would have long to wait. Huge, hideous, fat spiders spun cobwebs, of thousands of years' lasting, over their feet, webs like foot screws or manacles, which held them like copper chains; besides this, every soul was filled with everlasting unrest, an unrest of torment and pain. The miser stood there, lamenting that he had forgotten the key to his money box. Yes, it would take too long to repeat all the tortures and troubles of that place.

Inger was tortured by standing like a statue; it was as if she were fastened to the ground by the loaf of bread.

"This is what comes of trying to have clean feet," she said to herself. "Look at them stare at me!"

Yes, they all stared at her, with evil passions glaring from their eyes, and spoke without a sound coming from their mouths. They were frightful to look at!

"It must be a pleasure to look at me," thought little Inger. "I have a pretty face and nice clothes." And then she turned her eyes; her neck was too stiff to move. My, how soiled she had become in the Marsh Woman's brewery! Her dress was covered with clots of nasty slime; a snake had wound itself in her hair and dangled over her neck; and from every fold of her dress an ugly toad peeped out, barking like an asthmatic lap dog. It was most disagreeable. "But all the others down here look horrible, too," was the only way she could console herself.

Worst of all was the dreadful hunger she felt. Could she stoop down and break off a bit of the bread on which she was standing? No, her back had stiffened, her arms and hands had stiffened, her whole body was like a statue of stone. She could only roll her eyes, but these she could turn entirely around, so she could see behind her, and that was a horrid sight. Then the flies came and crept to and fro across her eyeballs. She blinked her eyes, but the flies did not fly away, for they could not; their wings had been pulled off, and they had become creeping insects. That was another torment added to the hunger, and at last it seemed to her as if part of her insides were eating itself up; she was so empty, so terribly empty.

"If this keeps up much longer, I won't be able to stand it!" she said.

But she had to stand it; her sufferings only increased.

Then a hot tear fell upon her forehead. It trickled over her face and neck, down to the bread at her feet. Then another tear fell, and many more followed. Who could be weeping for little Inger? Had she not a mother up there on earth? A mother's tears of grief for her erring child always reach it, but they do not redeem; they only burn, and they make the pain greater. And this terrible hunger, and being unable to snatch a mouthful of the bread she trod underfoot! She finally had a feeling that everything inside her must have eaten itself up. She became like a thin, hollow reed, taking in every sound.

She could hear distinctly everything that was said about her on the earth above, and what she heard was harsh and evil. Though her mother wept sorrowfully, she still said, "Pride goes before a fall. It was your own ruin, Inger. How you have grieved your mother!" Her mother and everyone else up there knew about her sin, that she had trod upon the bread and had sunk and stayed down; the cowherd who had seen it all from the brow of the hill told them.

"How you have grieved your mother, Inger!" said the mother. "Yes, I expected this!"

"I wish I had never been born!" thought Inger. "I would have been much better off. My mother's tears cannot help me now."

She heard how her employers, the good people who had been like parents to her, spoke. "She was a sinful child," they said. "She did not value the gifts of our Lord, but trampled them underfoot. It will be hard for her to have the gates of mercy opened to let her in."

"They ought to have brought me up better," Inger thought. "They should have beaten the nonsense out of me, if I had any."

She heard that a song had been written about her, "the haughty girl who stepped on a loaf to keep her shoes clean," and was being sung from one end of the country to the other.

"Why should I have to suffer and be punished so severely for such a little thing?" she thought. "The others certainly should be punished for their sins, too! But then, of course, there would be many to punish. Oh, how I am suffering!"

Then her mind became even harder than her shell-like form.

"No one can ever improve in this company! And I don't want to be any better. Look at them glare at me!"

Her heart became harder, and full of hatred for all mankind.

"Now they have something to talk about up there. Oh, how I am suffering!"

When she listened she could hear them telling her story to children as a warning, and the little ones called her "the wicked Inger." "She was so very nasty," they said, "so nasty that she deserved to be punished." The children had nothing but harsh words to speak of her.

But one day, when hunger and misery were gnawing at her hollow body, she heard her name mentioned and her story told to an innocent little girl, who burst into tears of pity for the haughty, clothes-loving Inger.

"But won't she ever come up again?" the child asked.

"She will never come up again, " they answered her.

"But if she would ask forgiveness and promise never to be bad again?"

"But she will not ask forgiveness," they said.

"Oh, how I wish she would!" the little girl said in great distress. "I'd give my doll's house if she could come up! It's so dreadful for poor Inger!"

These words reached right down to Inger's heart and seemed almost to make her good. For this was the first time anyone had said, "Poor Inger," and not added anything about her faults. An innocent little child had wept and prayed for her, and she was so touched by it that she wanted to weep herself, but the tears would not come, and that was also a torture.

The years passed up there, but down below there was no change. Inger heard fewer words from above; there was less talk about her. At last one day she heard a deep sigh, and the cry, "Inger, Inger, how miserable you have made me! I knew that you would!" Those were the dying words of her mother.

She heard her name mentioned now and then by her former mistress, and it was in the mildest way that she spoke: "I wonder if I will ever see you again, Inger! One never knows where one is to go!" But Inger knew that her kindly mistress would never descend to the place where she was.

Again a long time passed, slowly and bitterly. Then Inger heard her name again, and she beheld above her what seemed to be two bright stars shining down on her. They were two mild eyes that were closing on earth. So many years had passed since a little girl had wept over "Poor Inger" that that child had become an old woman, now being called by the Lord to Himself. At that last hour, when the thoughts and deeds of a lifetime pass in review, she remembered very clearly how, as a tiny child, she had wept over the sad story of Inger. That time and that sorrow were so intensely in the old woman's mind at the moment of death that she cried with all her heart, "My Lord, have I not often, like poor Inger, trampled underfoot Your blessed gifts and counted them of no value? Have I not often been guilty of the sin of pride and vanity in my inmost heart? But in Your mercy You did not let me sink into the abyss, but did sustain me! Oh, forsake me not in my final hour!"

Then the old woman's eyes closed, but the eyes of her soul were opened to things formerly hidden; and as Inger had been so vividly present in her last thoughts she could see the poor girl, see how deeply she had sunk. And at that dreadful sight the gentle soul burst into tears; in the kingdom of heaven itself she stood like a child and wept for the fate of the unhappy Inger. Her tears and prayers came like an echo down to the hollow, empty shape that held the imprisoned, tortured soul. And that soul was overwhelmed by all that unexpected love from above. One of God's angels wept for her! Why was this granted her?

The tormented soul gathered into one thought all the deeds of its earthly life, and trembled with tears, such tears as Inger had never wept before. Grief filled her whole being. And as in deepest humility she thought that for her the gates of mercy would never be opened, a brilliant ray penetrated down into the abyss to her; it was a ray more powerful than the sunbeams that melt the snowmen that boys make in their yards. And under this ray, more swiftly than the snowflake falling upon a child's warm lips melts into a drop of water, the petrified figure of Inger evaporated; then a tiny bird arose and followed the zigzag path of the ray up to the world of mankind.

But it seemed terrified and shy of all about it; as if ashamed and wishing to avoid all living creatures, it hastily concealed itself in a dark hole in a crumbling wall. There it sat trembling all over, and could utter no sound, for it had no voice. It sat for a long time before it dared to peer out and gaze at the beauty about; yes, there was beauty indeed. The air was so fresh and soft; the moon shone so clearly; the trees and flowers were so fragrant; and the bird sat in such comfort, with feathers clean and dainty. How all creation spoke of love and beauty! The bird wanted to sing out the thoughts that filled its breast, but it could not; gladly would it have sung like the nightingale or the cuckoo in the springtime. Our Lord, who hears the voiceless hymn of praise even from a worm, understood the psalm of thanksgiving that swelled in the heart of the bird, as the psalm echoed in the heart of David before it took shape in words.

For weeks these mute feelings of gratitude increased. Someday surely they would find a voice, perhaps with the first stroke of the wing performing some good deed. Could not this happen?

Now came the feast of holy Christmas. Close by the wall a farmer set up a pole and tied an unthreshed bundle of oats on it, that the fowls of the air might also have a merry Christmas, and a joyous meal in this, the day of our Saviour.

Brightly the sun rose that Christmas morning and shone down upon the oats and all the chirping birds that gathered around the pole. Then from the wall there came a faint "tweet, tweet." The swelling thoughts had at last found a voice, and the tiny sound was a whole song of joy as the bird flew forth from its hiding place; in the realm of heaven they well knew who this bird was.

The winter was unusually severe. The ponds were frozen over thickly; the birds and wild creatures of the forest had very little food. The tiny bird flew about the country roads, and whenever it chanced to find a few grains of corn fallen in the ruts made by the sleds, it would eat but a single grain itself, while calling the other hungry birds, that they might have some food. Then it would fly into the towns and search closely, and wherever kindly hands had strewed bread crumbs outside the windows for the birds, it would eat only a single crumb and give all the rest away.

By the end of the winter the bird had found and given away so many crumbs of bread that they would have equaled in weight the loaf upon which little Inger had stepped to keep her fine shoes from being soiled; and when it had found and given away the last crumb, the gray wings of the bird suddenly became white and expanded.

"Look, there flies a sea swallow over the sea!" the children said as they saw the white bird. Now it seemed to dip into the water; now it rose into the bright sunshine; it gleamed in the air; it was not possible to see what became of it; they said that it flew straight into the sun.

by Hans Christian Andersen

~Bluebeard

THERE was a man who had fine houses, both in town and country, a deal of silver and gold plate, embroidered furniture, and coaches gilded all over with gold. But this man was so unlucky as to have a bluebeard, which made him so frightfully ugly that all the women and girls ran away from him.

One of his neighbors, a lady of quality, had two daughters who were perfect beauties. He desired of her one of them in marriage, leaving to her choice which of the two she would bestow on him. They would neither of them have him, and sent him backward and forward from one another, not being able to bear the thoughts of marrying a man who had a blue beard, and what besides gave them disgust and aversion was his having already been married to several wives, and nobody ever knew what became of them.

Bluebeard, to engage their affection, took them, with the lady their mother and three or four ladies of their acquaintance, with other young people of the neighborhood, to one of his country seats, where they stayed a whole week.

There was nothing there to be seen but parties of pleasure, hunting, fishing, dancing, mirth, and feasting. Nobody went to bed, but all passed the night in rallying and joking with each other. In short, everything succeeded so well that the youngest daughter began to think the master of the house not to have a beard so very blue, and that he was a mighty civil gentleman.

As soon as they returned home, the marriage was concluded. About a month afterward, Bluebeard told his wife that he was obliged to take a country journey for six weeks at least, about affairs of very great consequence, desiring her to divert herself in his absence, to send for her friends and acquaintances, to carry them into the country, if she pleased, and to make good cheer wherever she was.

"Here," said he, "are the keys of the two great wardrobes, wherein I have my best furniture; these are of my silver and gold plate, which is not every day in use; these open my strong boxes, which hold my money, both gold and silver; these my caskets of jewels; and this is the master-key to all my apartments.

But for this little one here, it is the key of the closet at the end of the great gallery on the ground floor. Open them all; go into all and every one of them, except that little closet, which I forbid you, and forbid it in such a manner that, if you happen to open it, there's nothing but what you may expect from my just anger and resentment."

She promised to observe, very exactly, whatever he had ordered; when he, after having embraced her, got into his coach and proceeded on his journey.

Her neighbors and good friends did not stay to be sent for by the new married lady, so great was their impatience to see all the rich furniture of her house, not daring to come while her husband was there, because of his blue beard, which frightened them. They ran through all the rooms, closets, and wardrobes, which were all so fine and rich that they seemed to surpass one another.

After that they went up into the two great rooms, where was the best and richest furniture; they could not sufficiently admire the number and beauty of the tapestry, beds, couches, cabinets, stands, tables, and looking-glasses, in which you might see yourself from head to foot; some of them were framed with glass, others with silver, plain and gilded, the finest and most magnificent ever were seen.

They ceased not to extol and envy the happiness of their friend, who in the meantime in no way diverted herself in looking upon all these rich things, because of the impatience she had to go and open the closet on the ground floor. She was so much pressed by her curiosity that, without considering that it was very uncivil to leave her company, she went down a little back staircase, and with such excessive haste that she had twice or thrice like to have broken her neck.

Coming to the closet-door, she made a stop for some time, thinking upon her husband's orders, and considering what unhappiness might attend her if she was disobedient; but the temptation was so strong she could not overcome it. She then took the little key, and opened it, trembling, but could not at first see anything plainly, because the windows were shut. After some moments she began to perceive that the floor was all covered over with clotted blood, on which lay the bodies of several dead women, ranged against the walls. (These were all the wives whom Bluebeard had married and murdered, one after another.) She thought she should have died for fear, and the key, which she pulled out of the lock, fell out of her hand.

After having somewhat recovered her surprise, she took up the key, locked the door, and went upstairs into her chamber to recover herself; but she could not, she was so much frightened. Having observed that the key of the closet was stained with blood, she tried two or three times to wipe it off, but the blood would not come out; in vain did she wash it, and even rub it with soap and sand; the blood still remained, for the key was magical and she could never make it quite clean; when the blood was gone off from one side, it came again on the other.

Bluebeard returned from his journey the same evening, and said he had received letters upon the road, informing him that the affair he went about was ended to his advantage. His wife did all she could to convince him she was extremely glad of his speedy return.

Next morning he asked her for the keys, which she gave him, but with such a trembling hand that he easily guessed what had happened.

"What!" said he, "is not the key of my closet among the rest?"

"I must certainly have left it above upon the table," said she.

"Fail not to bring it to me presently," said Bluebeard.

After several goings backward and forward she was forced to bring him the key. Bluebeard, having very attentively considered it, said to his wife, "How comes this blood upon the key?"

"I do not know," cried the poor woman, paler than death.

"You do not know!" replied Bluebeard. "I very well know. You were resolved to go into the closet, were you not? Mighty well, madam; you shall go in, and take your place among the ladies you saw there."

Upon this she threw herself at her husband's feet, and begged his pardon with all the signs of true repentance, vowing that she would never more be disobedient. She would have melted a rock, so beautiful and sorrowful was she; but Bluebeard had a heart harder than any rock!

"You must die, madam," said he, "and that presently."

"Since I must die," answered she (looking upon him with her eyes all bathed in tears), "give me some little time to say my prayers."

"I give you," replied Bluebeard, "half a quarter of an hour, but not one moment more."

When she was alone she called out to her sister, and said to her: "Sister Anne" (for that was her name), "go up, I beg you, upon the top of the tower, and look if my brothers are not coming over; they promised me that they would come today, and if you see them, give them a sign to make haste."

Her sister Anne went up upon the top of the tower, and the poor afflicted wife cried out from time to time: "Anne, sister Anne, do you see anyone coming?"

And sister Anne said: "I see nothing but the sun, which makes a dust, and the grass, which looks green."

In the meanwhile Bluebeard, holding a great sabre in his hand, cried out as loud as he could bawl to his wife: "Come down instantly, or I shall come up to you."

"One moment longer, if you please," said his wife, and then she cried out very softly, "Anne, sister Anne, dost thou see anybody coming?"

And sister Anne answered: "I see nothing but the sun, which makes a dust, and the grass, which is green."

"Come down quickly," cried Bluebeard, "or I will come up to you."

"I am coming," answered his wife; and then she cried, "Anne, sister Anne, dost thou not see anyone coming?"

"I see," replied sister Anne, "a great dust, which comes on this side here."

"Are they my brothers?"

"Alas! no,my dear sister, I see a flock of sheep."

"Will you not come down?" cried Bluebeard.

"One moment longer," said his wife, and then she cried out: "Anne, sister Anne, dost thou see nobody coming?"

"I see," said she, "two horsemen, but they are yet a great way off."

"God be praised," replied the poor wife joyfully; "they are my brothers; I will make them a sign, as well as I can, for them to make haste."

Then Bluebeard bawled out so loud that he made the whole house tremble. The distressed wife came down, and threw herself at his feet, all in tears, with her hair about her shoulders.

"This signifies nothing," says Bluebeard; "you must die"; then, taking hold of her hair with one hand, and lifting up the sword with the other, he was going to take off her head. The poor lady, turning about to him, and looking at him with dying eyes, desired him to afford her one little moment to recollect herself.

"No, no," said he, "recommend thyself to God," and was just ready to strike . . .

At this very instant there was such a loud knocking at the gate that Bluebeard made a sudden stop. The gate was opened, and presently entered two horsemen, who, drawing their swords, ran directly to Bluebeard. He knew them to be his wife's brothers, one a dragoon, the other a musketeer, so that he ran away immediately to save himself; but the two brothers pursued so close that they overtook him before he could get to the steps of the porch, when they ran their swords through his body and left him dead. The poor wife was almost as dead as her husband, and had not strength enough to rise and welcome her brothers.

Bluebeard had no heirs, and so his wife became mistress of all his estate. She made use of one part of it to marry her sister Anne to a young gentleman who had loved her a long while; another part to buy captains commissions for her brothers, and the rest to marry herself to a very worthy gentleman, who made her forget the ill time she had passed with Bluebeard.

by Charles Perrault

~Pinocchio

Once upon a time...

a carpenter picked up a strange chunk of wood one day while mending a table. When he began to chip it, the wood started to moan. This frightened the carpenter and he decided to get rid of it at once, so he gave it to a friend called Geppetto, who wanted to make a puppet.

Geppetto, a cobbler, took his lump of wood home, thinking about the name he would give his puppet.

"I'll call him Pinocchio," he told himself. "It's a lucky name." Back in his humble basement home and workshop, Geppetto started to carve the wood. Suddenly a voice squealed:

"Ooh! That hurt!" Geppetto was astonished to find that the wood was alive. Excitedly he carved a head, hair and eyes, which immediately stared right at the cobbler. But the second Geppetto carved out the nose, it grew longer and longer, and no matter how often the cobbler cut it down to size, it just stayed a long nose. The newly cut mouth began to chuckle and when Geppetto angrily complained, the puppet stuck out his tongue at him.

That was nothing, however! When the cobbler shaped the hands, they snatched the good man's wig, and the newly carved legs gave him a hearty kick. His eyes brimming with tears, Geppetto scolded the puppet.

"You naughty boy! I haven't even finished making you, yet you've no respect for your father!" Then he picked up the puppet and, a step at a time, taught him to walk. But the minute Pinocchio stood upright, he started to run about the room, with Geppetto after him, then he opened the door and dashed into the street.

Now, Pinocchio ran faster than Geppetto and though the poor cobbler shouted "Stop him! Stop him!" none of the onlookers, watching in amusement, moved a finger. Luckily, a policeman heard the cobbler's shouts and strode quickly down the street. Grabbing the runaway, he handed him over to his father.

"I'll box your ears," gasped Geppetto, still out of breath.

Then he realized that was impossible, for in his haste to carve the puppet, he had forgotten to make his ears. Pinocchio had got a fright at being in the clutches of the police, so he apologized and Geppetto forgave his son.

Indeed, the minute they reached home, the cobbler made Pinocchio a suit out of flowered paper, a pair of bark shoes and a soft bread hat. The puppet hugged his father.

"I'd like to go to school," he said, "to become clever and help you when you're old!" Geppetto was touched by this kind thought.

"I'm very grateful," he replied, "but we haven't enough money even to buy you the first reading book!" Pinocchio looked downcast, then Geppetto suddenly rose to his feet, put on his old tweed coat and went out of the house. Not long after he returned carrying a first reader, but minus his coat. It was snowing outside.

"Where's your coat, father?" "I sold it."

"Why did you sell it?"

"It kept me too warm!"

Pinocchio threw his arms round Geppetto's neck and kissed the kindly old man.

It had stopped snowing and Pinocchio set out for school with his first reading book under his arm. He was full of good intentions. "Today I want to learn to read. Tomorrow I'll learn to write and the day after to count. Then I'll earn some money and buy Geppetto a fine new coat. He deserves it, for . . ." The sudden sound of a brass band broke into the puppet's daydream and he soon forgot all about school. He ended up in a crowded square where people were clustering round a brightly colored booth.

"What's that?" he asked a boy.

"Can't you read? It's the Great Puppet Show!"

"How much do you pay to go inside?"

"Fourpence.'

"Who'll give me fourpence for this brand new book?" Pinocchio cried. A nearby junk seller bought the reading book and Pinocchio hurried into the booth. Poor Geppetto. His sacrifice had been quite in vain. Hardly had Pinocchio got inside, when he was seen by one of the puppets on the stage who cried out: "There's Pinocchio! There's Pinocchio!"

"Come, along. Come up here with us. Hurrah for brother Pinocchio!" cried the puppets. Pinocchio went onstage with his new friends, while the spectators below began to mutter about uproar. Then out strode Giovanni, the puppet- master, a frightful looking man with fierce bloodshot eyes.

"What's going on here? Stop that noise! Get in line, or you'll hear about it later!"

That evening, Giovanni sat down to his meal, but when he found that more wood was needed to finish cooking his nice chunk of meat, he remembered the intruder who had upset his show.

"Come here, Pinocchio! You'll make good firewood!" The poor puppet started to weep and plead.

"Save me, father! I don't want to die . . . I don't want to die!"

When Giovanni heard Pinocchio's cries, he was surprised.

"Are your parents still alive?" he asked.

"My father is, but I've never known my mother," said the puppet in a low voice. The big man's heart melted.

"It would be beastly for your father if I did throw you into the fire . . . but I must finish roasting the mutton. I'll just have to burn another puppet. Men! Bring me Harlequin, trussed!" When Pinocchio saw that another puppet was going to be burned in his place, he wept harder than ever.

"Please don't, sir! Oh, sir, please don't! Don't burn Harlequin!"

"That's enough!" boomed Giovanni in a rage. "I want my meat well cooked!" "In that case," cried Pinocchio defiantly, rising to his feet, "burn me! It's not right that Harlequin should be burnt instead ofme!"

Giovanni was taken aback. "Well, well!" he said. "I've never met a puppet hero before!" Then he went on in a milder tone. "You really are a good lad. I might indeed . . ." Hope flooded Pinocchio's heart as the puppet- master stared at him, then at last the man said: "All right! I'll eat half raw mutton tonight, but next time, somebody will find himself in a pickle." All the puppets were delighted at being saved. Giovanni asked Pinocchio to tell him the whole tale, and feeling sorry for kindhearted Geppetto, he gave the puppet five gold pieces.

"Take these to your father," he said. "Tell him to buy himself a new coat, and give him my regards."

Pinocchio cheerfully left the puppet booth after thanking Giovanni for being so generous. He was hurrying homewards when he met a half blind cat and a lame fox. He couldn't help but tell them all about his good fortune, and when the pair set eyes on the gold coins, they hatched a plot, saying to Pinocchio:

"If you would really like to please your father, you ought to take him a lot more coins. Now, we know of a magic meadow where you can sow these five coins. The next day, you will find they have become ten times as many!"

"How can that happen?" asked Pinocchio in amazement.

"I'll tell you how!" exclaimed the fox. "In the land of Owls lies a meadow known as Miracle Meadow. If you plant one gold coin in a little hole, next day you will find a whole tree dripping with gold coins!"

Pinocchio drank in every word his two "friends" uttered and off they all went to the Red Shrimp Inn to drink to their meeting and future wealth.

After food and a short rest, they made plans to leave at midnight for Miracle Meadow. However, when Pinocchio was wakened by the innkeeper at the time arranged, he found that the fox and the cat had already left. All the puppet could do then was pay for the dinner, using one of his gold coins, and set off alone along the path through the woods to the magic meadow. Suddenly...

"Your money or your life!" snarled two hooded bandits. Now, Pinocchio had hidden the coins under his tongue, so he could not say a word, and nothing the bandits could do would make Pinocchio tell where the coins were hidden. Still mute, even when the wicked pair tied a noose round the poor puppet's neck and pulled it tighter and tighter, Pinocchio's last thought was "Father, help me!"

Of course, the hooded bandits were the fox and the cat. "You'll hang there," they said, "till you decide to talk. We'll be back soon to see if you have changed your mind!" And away they went.

However, a fairy who lived nearby had overheard everything . . . From the castle window, the Turquoise Fairy saw a kicking puppet dangling from an oak tree in the wood. Taking pity on him, she clapped her hands three times and suddenly a hawk and a dog appeared.

"Quickly!" said the fairy to the hawk. "Fly to that oak tree and with your beak snip away the rope round the poor lad's neck!"

To the dog she said: "Fetch the carriage and gently bring him to me!"

In no time at all, Pinocchio, looking quite dead, was lying in a cozy bed in the castle, while the fairy called three famous doctors, crow, owl and cricket. A very bitter medicine, prescribed by these three doctors quickly cured the puppet, then as she caressed him, the fairy said: "Tell me what happened!"

Pinocchio told her his story, leaving out the bit about selling his first reading book, but when the fairy asked him where the gold coins were, the puppet replied that he had lost them. In fact, they were hidden in one of his pockets. All at once, Pinocchio's nose began to stretch, while the fairy laughed.

"You've just told a lie! I know you have, because your nose is growing longer!" Blushing with shame, Pinocchio had no idea what to do with such an ungainly nose and he began to weep.

However, again feeling sorry for him, the fairy clapped her hands and a flock of woodpeckers appeared to peck his nose back to its proper length.

"Now, don't tell any more lies," the fairy warned him," or your nose will grow again! Go home and take these coins to your father."

Pinocchio gratefully hugged the fairy and ran off homewards.

But near the oak tree in the forest, he bumped into the cat and the fox. Breaking his promise, he foolishly let himself be talked into burying the coins in the magic meadow. Full of hope, he returned next day, but the coins had gone. Pinocchio sadly trudged home without the coins Giovanni had given him for his father.

After scolding the puppet for his long absence, Geppetto forgave him and off he went to school. Pinocchio seemed to have calmed down a bit. But someone else was about to cross his path and lead him astray. This time, it was Carlo, the lazy bones of the class.

"Why don't you come to Toyland with me?" he said. "Nobody ever studies there and you can play all day long!"

"Does such a place really exist?" asked Pinocchio in amazement. "The wagon comes by this evening to take me there," said Carlo. "Would you like to come?"

Forgetting all his promises to his father and the fairy, Pinocchio was again heading for trouble. Midnight struck, and the wagon arrived to pick up the two friends, along with some other lads who could hardly wait to reach a place where schoolbooks and teachers had never been heard of. Twelve pairs of donkeys pulled the wagon, and they were all shod with white leather boots.

The boys clambered into the wagon. Pinocchio, the most excited of them all, jumped on to a donkey. Toyland, here we come!

Now Toyland was just as Carlo had described it: the boys all had great fun and there were no lessons. You weren't even allowed to whisper the word "school", and Pinocchio could hardly believe he was able to play allthe time.

"This is the life!" he said each time he met Carlo.

"I was right, wasn't I?" exclaimed his friend, pleased with himself.

"Oh, yes Carlo! Thanks to you I'm enjoying myself. And just think: teacher told me to keep well away from you."

One day, however, Pinocchio awoke to a nasty surprise.

When he raised a hand to his head, he found he had sprouted a long pair of hairy ears, in place of the sketchy ears that Geppetto had never got round to finishing. And that wasn't all!

The next day, they had grown longer than ever. Pinocchio shamefully pulled on a large cotton cap and went off to search for Carlo. He too was wearing a hat, pulled right down to his nose. With the same thought in their heads, the boys stared at each other, then snatching off their hats, they began to laugh at the funny sight of long hairy ears. But as they screamed with laughter, Carlo suddenly went pale and began to stagger. "Pinocchio, help! Help!" But Pinocchio himself was stumbling about and he burst into tears. For their faces were growing into the shape of a donkey's head and they felt themselves go down on all fours. Pinocchio and Carlo were turning into a pair of donkeys. And when they tried to groan with fear, they brayed loudly instead. When the Toyland wagon driver heard the braying of his new donkeys, he rubbed his hands in glee.

"There are two fine new donkeys to take to market. I'll get at least four gold pieces for them!" For such was the awful fate that awaited naughty little boys that played truant from school to spend all their time playing games.

Carlo was sold to a farmer, and a circus man bought Pinocchio to teach him to do tricks like his other performing animals. It was a hard life for a donkey! Nothing to eat but hay, and when that was gone, nothing but straw. And the beatings! Pinocchio was beaten every day till he had mastered the difficult circus tricks. One day, as he was jumping through the hoop, he stumbled and went lame. The circus man called the stable boy.

"A lame donkey is no use to me," he said. "Take it to market and get rid of it at any price!" But nobody wanted to buy a useless donkey. Then along came a little man who said: "I'll take it for the skin. It will make a good drum for the village band!"

And so, for a few pennies, Pinocchio changed hands and he brayed sorrowfully when he heard what his awful fate was to be. The puppet's new owner led him to the edge of the sea, tied a large stone to his neck, and a long rope round Pinocchio's legs and pushed him into the water. Clutching the end of the rope, the man sat down to wait for Pinocchio to drown. Then he would flay off the donkey's skin.

Pinocchio struggled for breath at the bottom of the sea, and in a flash, remembered all the bother he had given Geppetto, his broken promises too, and he called on the fairy.

The fairy heard Pinocchio's call and when she saw he was about to drown, she sent a shoal of big fish. They ate away all the donkey flesh, leaving the wooden Pinocchio. Just then, as the fish stopped nibbling, Pinocchio felt himself hauled out of the water. And the man gaped in astonishment at the living puppet, twisting and turning like an eel, which appeared in place of the dead donkey. When he recovered his wits, he babbled, almost in tears: "Where's the donkey I threw into the sea?"

"I'm that donkey", giggled Pinocchio.

"You!" gasped the man. "Don't try pulling my leg. If I get angry . . ."

However, Pinocchio told the man the whole story . . . "and that's how you come to have a live puppet on the end of the rope instead of a dead donkey!"

"I don't give a whit for your story," shouted the man in a rage.

"All I know is that I paid twenty coins for you and I want my money back! Since there's no donkey, I'll take you to market and sell you as firewood!"

By then free of the rope, Pinocchio made a face at the man and dived into the sea. Thankful to be a wooden puppet again, Pinocchio swam happily out to sea and was soon just a dot on the horizon. But his adventures were far from over. Out of the water behind him loomed a terrible giant shark! A horrified Pinocchio saw its wide open jaws and tried to swim away as fast as he could, but the monster only glided closer. Then the puppet tried to escape by going in the other direction, but in vain. He could never escape the shark, for as the water rushed into its cavern like mouth, he was sucked in with it. And in an instant Pinocchio had been swallowed along with shoals of fish unlucky enough to be in the fierce creature's path. Down he went, tossed in the torrent of water as it poured down the shark's throat, till he felt dizzy.

When Pinocchio came to his senses, he was in darkness.

Over his head, he could hear the loud heave of the shark's gills.

On his hands and knees, the puppet crept down what felt like a sloping path, crying as he went:

"Help! Help! Won't anybody save me?"

Suddenly, he noticed a pale light and, as he crept towards it, he saw it was a flame in the distance. On he went, till: "Father! It can't be you! . . "Pinocchio! Son! It really is you . . ."

Weeping for joy, they hugged each other and, between sobs, told their adventures. Geppetto stroked the puppet's head and told him how he came to be in the shark's stomach.

"I was looking for you everywhere. When I couldn't find you on dry land, I made a boat to search for you on the sea. But the boat capsized in a storm, then the shark gulped me down.

Luckily, it also swallowed bits of ships wrecked in the tempest, so I've managed to survive by getting what I could from these!"

"Well, we're still alive!" remarked Pinocchio, when they had finished recounting their adventures. "We must get out of here!"

Taking Geppetto's hand, the pair started to climb up the shark's stomach, using a candle to light their way.

When they got as far as its jaws, they took fright, but as so happened, this shark slept with its mouth open, for it suffered from asthma.

As luck would have it, the shark had been basking in shallow waters since the day before, and Pinocchio soon reached the beach. Dawn was just breaking, and Geppetto, soaked to the skin, was half dead with cold and fright.

"Lean on me, father." said Pinocchio. "I don't know where we are, but we'll soon find our way home!"

Beside the sands stood an old hut made of branches, and there they took shelter. Geppetto was running a temperature, but Pinocchio went out, saying, "I'm going to get you some milk."

The bleating of goats led the puppet in the right direction, and he soon came upon a farmer. Of course, he had no money to pay for the milk.

"My donkey's dead," said the farmer. "If you work the treadmill from dawn to noon, then you can have some milk." And so, for days on end, Pinocchio rose early each morning to earn Geppetto's food.

At long last, Pinocchio and Geppetto reached home.

The puppet worked late into the night weaving reed baskets to make money for his father and himself. One day, he heard that the fairy after a wave of bad luck, was ill in hospital. So instead of buying himself a new suit of clothes, Pinocchio sent the fairy the money to pay for her treatment.

One night, in a wonderful dream, the fairy appeared to reward Pinocchio for his kindness. When the puppet looked in the mirror next morning, he found he had turned into somebody else. For there in the mirror, was a handsome young lad with blue eyes and brown hair. Geppetto hugged him happily.

"Where's the old wooden Pinocchio?" the young lad asked in astonishment. "There!" exclaimed Geppetto, pointing at him. "When bad boys become good, their looks change along with their lives!"

By The Brothers Grimm

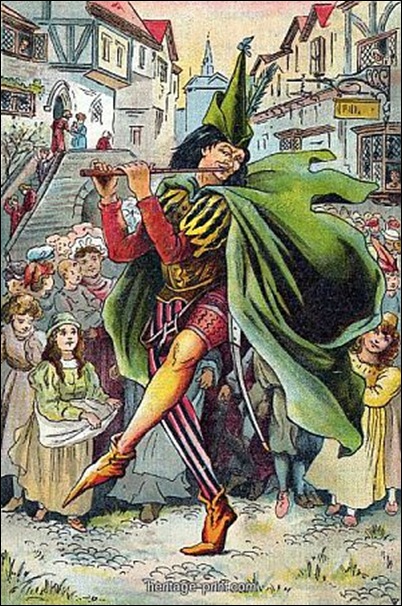

~The Pied Piper of Hamelin

Once upon a time...

on the banks of a great river in the north of Germany lay a town called Hamelin. The citizens of Hamelin were honest folk who lived contentedly in their Grey stone houses. The years went by, and the town grew very rich.

Then one day, an extraordinary thing happened to disturb the peace.

Hamelin had always had rats, and a lot too. But they had never been a danger, for the cats had always solved the rat problem in the usual way- by killing them. All at once, however, the rats began to multiply.

In the end, a black sea of rats swarmed over the whole town. First, they attacked the barns and storehouses, then, for lack of anything better, they gnawed the wood, cloth or anything at all. The one thing they didn't eat was metal. The terrified citizens flocked to plead with the town councilors to free them from the plague of rats. But the council had, for a long time, been sitting in the Mayor's room, trying to think of a plan.

"What we need is an army of cats!"

But all the cats were dead.

"We'll put down poisoned food then . . ."

But most of the food was already gone and even poison did not stop the rats.

"It just can't be done without help!" said the Mayor sadly.

Just then, while the citizens milled around outside, there was a loud knock at the door. "Who can that be?" the city fathers wondered uneasily, mindful of the angry crowds. They gingerly opened the door. And to their surprise, there stood a tall thin man dressed in brightly colored clothes, with a long feather in his hat, and waving a gold pipe at them.

"I've freed other towns of beetles and bats," the stranger announced, "and for a thousand florins, I'll rid you of your rats!"

"A thousand florins!" exclaimed the Mayor. "We'll give you fifty thousand if you succeed!" At once the stranger hurried away, saying:

"It's late now, but at dawn tomorrow, there won't be a rat left in Hamelin!"

The sun was still below the horizon, when the

sound of a pipe wafted through the streets of Hamelin. The pied piper slowly made his way through the houses and behind him flocked the rats. Out they scampered from doors, windows and gutters, rats of every size, all after the piper. And as he played, the stranger marched down to the river and straight into the water, up to his middle. Behind him swarmed the rats and every one was drowned and swept away by the current.

By the time the sun was high in the sky, there was not a single rat in the town. There was even greater delight at the town hall, until the piper tried to claim his payment.

"Fifty thousand florins?" exclaimed the councilors,

"Never..."

" A thousand florins at least!" cried the pied piper angrily. But the Mayor broke in. "The rats are all dead now and they can never come back. So be grateful for fifty florins, or you'll not get even that . . ."

His eyes flashing with rage, the pied piper pointed a threatening finger at the Mayor.

"You'll bitterly regret ever breaking your promise," he said, and vanished.

A shiver of fear ran through the councilors, but the Mayor shrugged and said excitedly: "We've saved fifty thousand florins!"

That night, freed from the nightmare of the rats, the citizens of Hamelin slept more soundly than ever. And when the strange sound of piping wafted through the streets at dawn, only the children heard it. Drawn as by magic, they hurried out of their homes. Again, the pied piper paced through the town, this time, it was children of all sizes that flocked at his heels to the sound of his strange piping.

The long procession soon left the town and made its way through the wood and across the forest till it reached the foot of a huge mountain. When the piper came to the dark rock, he played his pipe even louder still and a great door creaked open. Beyond lay a cave. In trooped the children behind the pied piper, and when the last child had gone into the darkness, the door creaked shut.

A great landslide came down the mountain blocking the entrance to the cave forever. Only one little lame boy escaped this fate. It was he who told the anxious citizens, searching for their children, what had

happened. And no matter what people did, the mountain never gave up its victims.

Many years were to pass before the merry voices of other children would ring through the streets of Hamelin but the memory of the harsh lesson lingered in everyone's heart and was passed down from father to son through the centuries.

By the Brothers Grimm

~Sun, Moon, and Talia

THERE was once a great Lord, who, having a daughter born to him named Talia, commanded the seers and wise men of his kingdom to come and tell him her fortune; and after various counsellings they came to the conclusion, that a great peril awaited her from a piece of stalk in some flax. Thereupon he issued a command, prohibiting any flax or hemp, or such-like thing, to be brought into his house, hoping thus to avoid the danger.

When Talia was grown up, and was standing one day at the window, she saw an old woman pass by who was spinning.

She had never seen a distaff or a spindle, and being vastly pleased with the twisting and twirling of the thread, her curiosity was so great that she made the old woman come upstairs.

Then, taking the distaff in her hand, Talia began to draw out the thread, when, by mischance, a piece of stalk in the flax getting under her finger-nail, she fell dead upon the ground;

at which sight the old woman hobbled downstairs as quickly as she could.

When the unhappy father heard of the disaster that had befallen Talia, after weeping bitterly, he placed her in that palace in the country, upon a velvet seat under a canopy of brocade; and fastening the doors, he quitted for ever the place which had been the cause of such misfortune to him, in order to drive all remembrance of it from his mind.

Now, a certain King happened to go one day to the chase,

and a falcon escaping from him flew in at the window of that palace. When the King found that the bird did not return at his call, he ordered his attendants to knock at the door,

thinking that the palace was inhabited; and after knocking for some time, the King ordered them to fetch a vine-dresser's ladder, wishing himself to scale the house and see what was inside.

Then he mounted the ladder, and going through the whole palace, he stood aghast at not finding there any living person.

At last he came to the room where Talia was lying, as if enchanted; and when the King saw her, he

called to her, thinking that she was asleep, but in vain, for she still slept on, however loud he called. So, after admiring her beauty awhile, the King returned home to his kingdom, where for a long time he forgot all that had happened.

Meanwhile, two little twins, one a boy and the other a girl, who looked like two little jewels, wandered, from I know not where, into the palace and found Talia in a trance.

At first they were afraid because they tried in vain to awaken her; but, becoming bolder, the girl gently took Talia's finger into her mouth, to bite it and wake her up by this means; and so it happened that the splinter of flax came out.

There upon she seemed to awake as from a deep sleep; and when she saw those little jewels at her side, she took them to her heart, and loved them more than her life; but she wondered greatly at seeing herself quite alone in the palace with two children, and food and refreshment brought her by unseen hands.

After a time the King, calling Talia to mind, took occasion one day when he went to the chase to go and see her; and when he found her awakened, and with two beautiful little creatures by her side, he was struck dumb with rapture. Then the King told Talia who he was, and they formed a great league and friendship, and he remained there for several days, promising, as he took leave, to return and fetch her.

When the King went back to his own kingdom he was for ever repeating the names of Talia and the little ones, insomuch that, when he was eating he had Talia in his mouth, and Sun and Moon (for so he named the children); nay, even when he went to rest he did not leave off calling on them, first one and then the other.

Now the King's stepmother had grown suspicious at his long absence at the chase, and when she heard him calling thus on Talia, Sun, and Moon, she waxed wroth, and said to the King's secretary, "Hark ye, friend, you stand in great danger, between the axe and the block; tell me who it is that my stepson is enamoured of, and I will make you rich; but if you conceal the truth from me, I'll make you rue it."

The man, moved on the one side by fear, and on the other pricked by interest, which is a bandage to the eyes of honour, the blind of justice, and an old horse-shoe to trip up good faith, told the Queen the whole truth. Whereupon she sent the secretary in the King's name to Talia, saying that he wished to see the children. Then Talia sent them with great joy, but the Queen commanded the cook to kill them, and serve them up in various ways for her wretched stepson to eat.

Now the cook, who had a tender heart, seeing the two pretty little golden pippins, took compassion on them, and gave them to his wife, bidding her keep them concealed; then he killed and dressed two little kids in a hundred different ways. When the King came, the Queen quickly ordered the dishes served up; and the King fell to eating with great delight, exclaiming,

"How good this is! Oh, how excellent, by the soul of my grandfather!" And the old Queen all the while kept saying,

"Eat away, for you know what you eat." At first the King paid no attention to what she said; but at last, hearing the music continue, he replied, "Ay, I know well enough what I eat, for YOU brought nothing to the house." And at last,

getting up in a rage, he went off to a villa at a little distance to cool his anger.

Meanwhile the Queen, not satisfied with what she had done, called the secretary again, and sent him to fetch Talia, pretending that the King wished to see her. At this summons Talia went that very instant, longing to see the light of her eyes, and not knowing that only the smoke awaited her. But when she came before the Queen, the latter said to her, with the face of a Nero, and full of poison as a viper, "Welcome, Madam Sly-cheat! Are you indeed the pretty mischief-maker? Are you the weed that has caught my son's eye and given me all this trouble."

When Talia heard this she began to excuse herself; but the Queen would not listen to a word; and having a large fire lighted in the courtyard, she commanded that Talia should be thrown into the flames. Poor Talia, seeing matters come to a bad pass, fell on her knees before the Queen, and besought her at least to grant her time to take the clothes from off her back. Whereupon the Queen, not so much out of pity for the unhappy girl, as to get possession of her dress, which was embroidered all over with gold and pearls, said to her, "Undress yourself--I allow you."

Then Talia began to undress, and as she took off each garment she uttered an exclamation of grief; and when she had stripped off her cloak, her gown, and her jacket, and was proceeding to take off her petticoat, they seized her and were dragging her away.

At that moment the King came up, and seeing the spectacle he demanded to know the whole truth;

and when he asked also for the children, and heard that his stepmother had ordered them to be killed, the unhappy King gave himself up to despair.

He then ordered her to be thrown into the same fire which had been lighted for Talia, and the secretary with her, who was the handle of this cruel game and the weaver of this wicked web.

Then he was going to do the same with the cook, thinking that he had killed the children; but the cook threw himself at the King's feet and said, "Truly, sir King, I would desire no other sinecure in return for the service I have done you than to be thrown into a furnace full of live coals; I would ask no other gratuity than the thrust of a spike; I would wish for no other amusement than to be roasted in the fire; I would desire no other privilege than to have

the ashes of the cook mingled with those of a Queen. But I look for no such great reward for having saved the children, and brought them back to you in spite of that wicked creature who wished to kill them"

When the King heard these words he was quite beside himself;

he appeared to dream, and could not believe what his ears had heard. Then he said to the cook, "If it is true that you have saved the children, be assured I will take you from turning the spit,

and reward you so that you shall call yourself the happiest man in the world."

As the King was speaking these words, the wife of the cook, seeing the dilemma her husband was in, brought Sun and Moon before the King, who, playing at the game of three with Talia and the other children, went round and round kissing first one and then another. Then giving the cook a large reward, he made him his chamberlain; and he took Talia to wife, who enjoyed a long life with her husband and the children, acknowledging that--

"He who has luck may go to bed,

And bliss will rain upon his head."

by Giambattista Basile

~The Tale of Peter Rabbit

Once upon a time there were four little rabbits, and their names were Flopsy, Mopsy, Cotton-tail and Peter.

They lived with their mother in a sand-bank, underneath the root of a very big fir tree. "Now, my dears," said old Mrs. Rabbit one morning, "You may go into the fields or down the lane, but don't go into Mr. McGregor's garden.

Your father had an accident there; he was put in a pie by Mrs. McGregor."

Now run along and don't get into mischief. I am going out."

Then old Mrs. Rabbit took a basket and her umbrella and went through the wood to the baker's. She bought a loaf of brown bread and five currant buns.

Flopsy, Mopsy and Cotton-tail who were good little bunnies went down the lane together To gather blackberries. But Peter who was very naughty, ran straight away to Mr. McGregor's garden and Squeezed under the gate!

First he ate some lettuces and some French beans And then

He Ate Some Radishes

And then, feeling rather sick, he went to look for some parsley.

But round the end of a cucumber frame, whom should he meet but Mr. McGregor!

Mr. McGregor was on his hands and knees planting out young cabbages, but he jumped up and ran after Peter, waving a rake and calling out "Stop thief!"

Peter was most dreadfully frightened; he rushed all over the garden, for he had forgotten the way back to the gate.

He lost one shoe among the cabbages, and the other amongst the potatoes.

After losing them, he ran on four legs and went faster

So that I think he might have got away altogether if he had not unfortunately run into a gooseberry net

And got caught by the large buttons on his jacket.

It was a blue jacket with brass buttons, quite new.

Peter gave himself up for lost and shed big tears;

But his sobs were overheard by some friendly sparrows.

Who flew to him in great excitement and implored him to exert himself.

Mr. McGregor came up with a sieve which he intended to pop on the top of Peter, but Peter wriggled out just in time.

Leaving his jacket behind him. He rushed into the tool-shed and— Jumped into a can.

It would have been a beautiful thing to hide in, if it had not had so much water in it. Mr. McGregor was quite sure that Peter was somewhere in the tool-shed, perhaps hidden underneath a flower-pot.

He began to turn them over carefully, looking under each.

Presently Peter sneezed "Kertyschoo!"

Mr. McGregor was after him in no time, and tried to put his foot upon Peter, who Jumped out of a window, upsetting three plants.

Peter sat down to rest; he was out of breath and trembling with fright, and he had not the least idea which way to go.

Also he was very damp with sitting in that can.

After a time he began to wander about, going lippity—

lippity—

not very fast and looking all around. He found a door in a wall; but it was locked and there was no room for a fat little rabbit to squeeze underneath.

An old mouse was running in and out over the stone doorstep, carrying peas and beans to her family in the wood. Peter asked her the way to the gate but she had such a large pea in her mouth she could not answer. She only shook her head at him.

Peter began to cry.

Then he tried to find his way straight across the garden, but he became more and more puzzled. Presently he came to a pond where Mr. McGregor filled his water-cans. A white cat was staring at some gold-fish; she sat very, very still, but now and then the tip of her tail twitched as if it were alive. Peter thought it best to go away without speaking to her.

He had heard about cats from his cousin, little Benjamin Bunny.

He went back towards the tool-shed, but suddenly, quite close to him, he heard the noise of a hoe—scr-r-ritch, scratch, scratch, scritch.

Peter scuttered underneath the bushes, but presently as nothing happened, he came out and

Climbed upon a wheelbarrow, and peeped over.